Captivated by the majestic oceans, people have been compelled to go beneath the sea for centuries!

This fantastic underwater world, of which we still know so very little about, comprises the largest area of the globe. The oceans cover 71% of the earth’s surface, yet more than 95% of this vast expanse has not yet been explored. In fact over 60% of the oceans are called the Deep Seas, waters that are more than a mile in depth.

People have explored the seas since ancient times discovering rich minerals, plants, fish and a myriad of other animals. These all seem familiar today, yet as recently as the 1990’s two new animal habitats have been discovered in deep sea regions alone, each with its own unique ecosystem. In these deep underwater worlds sunlight is a very limited source of energy. Rather sulfites and methane are the life sustaining elements in these habitats, and the animals there are prosperous and thriving.

History of Diving Museum

History of Diving MuseumIn a recent trip to the Florida Keys, the opportunity to visit the History of Diving Museum gave me a glimpse into the incredible journey of diving.

The museum displays wondrous artifacts and historic dive equipment developed through the ages. Founders, Drs. Joe and Sally Bauer also amassed a comprehensive collection of rare books, prints, woodcuts, catalogues, and photographs that are relative to the story of undersea exploration. Some very early publications date back to the 1700s.

This underwater adventure started thousands of years ago and is still advancing today!

Free diving

Free diving is also known as breath-hold diving, apnea, and skin diving. This form of diving relies on the swimmer’s ability to hold their breath until resurfacing. It’s done without the aid of any type of breathing apparatus.

Ancient manuscripts and century old artifacts contain depictions of divers as early as 5000 BC. In these ancient times the reasons for diving probably started at first to gather food. The oldest archaeological evidence dates back to at least 5,400 BC. Excavated kitchen mittens from the time of the Scandinavian Stone Age culture, known as “Ertebolle,” show evidence of these ancient people being shellfish eating free divers.

Ancient Pearl Divers

Ancient Pearl DiversDiving was also done to harvest resources like sponge, pearl, and shells. The famous Ama divers from Japan began to collect pearls around 2,000 years ago. Interestingly, pearl diving is still practiced today in much the same fashion as in ancient times. Other early divers collected sunken “treasures” and provided aid in military campaigns.

These early divers faced the same problems divers deal with today. Aristotle was the first to document the common problems associated with diving, citing nose bleeding and pain in the ears. Decompression sickness or black outs during breath holding could be quite deadly in these ancient times.

Modern free diving activities include hunting techniques like spear fishing, and photography diving. There are also underwater games such as free diving football, hockey, and rugby. However some of the most exiting free diving today is as a competitive (and non-competitive) sport. Two of the world associations that govern competitive free diving are AIDA International, Association International for Development of Apnea, and CMAS World Underwater Federation.

Competitive modern free divers have held their breath for more than 10 minutes, swam further than 250 meters in length and gone beyond 200 meters in depth, all on a single breath of air. The men’s World record is held by Herbert Nitsch of Spetses, Greece, descending to a depth of 214 meters during a No-limits apnea (NLT) dive on 2007-06-14. The women’s World record is held by Tanya Streeter of Turks and Caicos, holder, descending to a depth of 160 meters during a No-limits apnea (NLT) dive on 2002-08-17.

Leather Diving Hood and Snorkel

Leather Diving Hood and SnorkelDiving with surface air

There were no mechanical devices to aid early divers but some simple means were devised to provide an air supply. These included the occasional use of hollow reeds used as a snorkel and carrying leather breathing bladders, basically inflated bags of air. These devices greatly limited the depth as well as the length of time a diver could stay underwater.

A tale by the famous Greek historian Herodotus tells the story of Scyllis and his daughter Cyan during the Greek-Persian wars in 500 BC. They swam under water at night to cut the anchor ropes of the Persian war ships. By using a hollow reed as a snorkel they were able to stay submerged and thus remain unobserved.

Modern Snuba Diving, Photo Wiki Commons, courtesy Jim Mayfield

Modern Snuba Diving, Photo Wiki Commons, courtesy Jim MayfieldAncient depictions of a leather hood and snorkel are found in the 1535 edition of Vegetieus’ book on war machines, “De Re Militari.” However this device is not said to have worked because water pressure would have collapsed the tube and a diver would not have been able to suck down air at depths of more than 1 or 2 feet. Renaissance scientist Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) designed such a hood as well.

Diving with surface air is still very popular in modern times. It comes in the form of Snuba Diving! This is an ideal method for people who don’t want to free dive, nor go to the efforts involved with scuba diving.

Bell diving and helmets

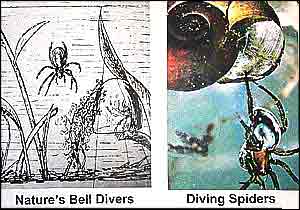

Diving Bell Spider, Argyroneta aquatica

Diving Bell Spider, Argyroneta aquaticaWhen it comes to diving creations however, humans are not alone!

People may have even been inspired by one of nature’s creatures, the Diving Bell Spider Argyroneta aquatica. These spiders are one of natures wonders that also dive, using an oxygen supply below water. They actually spend 99% of their entire life under the surface.

The Diving Bell Spider’s spin their strong spider silk tightly into a bell shape between the roots and stems of aquatic plants. Then using the hairs on their legs and abdomen, they trap air bubbles and fill this ‘diving bell’ web with air.

Alexander the Great is Lowered into the Sea

Alexander the Great is Lowered into the SeaThe diving bell is a rigid chamber that is filled with air.

It is used to transport divers under the water’s surface, even to the bottom of the sea, and allow them to breathe for extended periods of time. The most common types today are the wet bell and the closed bell.

Early use of diving bells is recorded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle in the 4th century BC. History also depicts Alexander the Great lowered into the sea in 332 BC, using a wooden barrel as a diving bell to clear the harbor at Tyre.

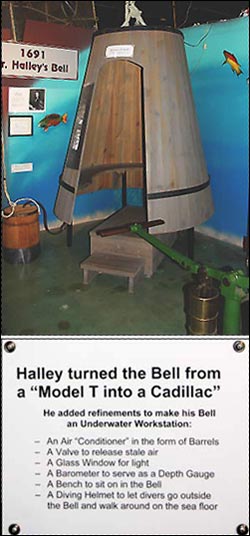

Halley’s Diving Bell

Halley’s Diving BellBut it wasn’t until around 1535, when an Italian named Guglielmo de Lorena designed, built, and used the first modern diving bell.

Lorena’s design is thought to have been derived from Aristotle’s early descriptions. It was a large “bell” that rested on the diver’s shoulders with a tube reaching to the surface that piped down fresh air.

Primitive diving bells were “bell-like” in shape and they were held stationary a few feet from the ocean substrate. The top portion of the bell contained air that was compressed by water pressure while the bottom was open.

This allowed a diver to stand upright within the bell and then leave for a short period of time to explore or collect items.

The diver could repeatedly return to the bell until the air in the bell was no longer breathable.

In the 16th century more people began to use diving bells and a variety of designs were developed.

Some of the most notable diving creations were designed by Dr. Edmond Halley in 1691.

Halley developed both a diving bell and the first diving helmet.

Halley’s Diving Helmet

Halley’s Diving Helmet- Halley’s Diving Bell

Halley’s diving bell had a window and the air was replenished by sending weighted barrels of fresh air down from the surface. - Halley’s Diving Helmet

Halley’s diving bell had a window and the air was replenished by sending weighted barrels of fresh air down from the surface.

Halley’s diving bell design was later improved on by Charles Spalding of Edinburgh in 1775.

To make the bell easier to raise and lower, Spalding added a system of balance-weights. Unfortunately Spalding and his nephew, Ebenezer Watson, had a tragic ending. In 1783 they suffocated in their diving bell while doing salvage work off the coast of Dublin.

Early Rigid Helmets for Diving

Early Rigid Helmets for DivingHuman adventurer’s are not to be thwarted, however, and these initial attempts soon led to a number of creative inventions.

All sorts of rigid helmets were being conceived across the world, and contemporary styles are still being used today!

Early self-contained diving

The ultimate success, and precursor to Scuba, was the move from utilizing surface air to a self-contained diving helmet!

Self-contained diving is where the diver carries his own air!

Thus we see the development of rebreathers and rigid-helmet diving suits.

Diving advances from Surface air to self-contained units

Diving advances from Surface air to self-contained unitsThe first crude rebreather is suggested to have been made around 1620 by Cornelius Drebbel, and the first air pump was built by Otto von Guericke in 1650. But the actual first successful rebreather was built in 1878 by an Englishman merchant seaman, Henry Fleuss as part of a self-contained diving rig that used compressed oxygen.

In 1808, Brizé-Fradin designed a small bell-like helmet connected to a low-pressure backpack air container. Then in 1825 that English inventor William James conceived the first workable self-contained design with an iron air reservoir secured around the diver’s waist. However the first functional self-contained diving system was manufactured and used by Charles Condert of Brooklyn, New York in 1831.

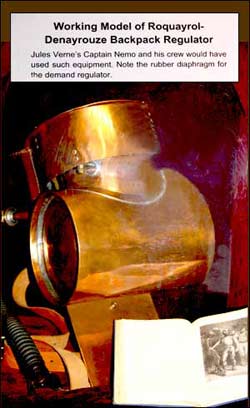

Working model of Rouquayrol-Denayrouze backpack regulator

Working model of Rouquayrol-Denayrouze backpack regulatorScuba diving

The first Scuba apparatus to be developed in history of scuba diving, called the Aerophore, was designed by Benoit Rouquayrol and Auguste Denayrouze in 1865. It is similar to earlier designs and included a diving helmet, a compressed air tank, and an early rudimentary demand regulator.

This apparatus primarily used surface air but could also function independently, yet the diver still walked on the seabed and did not swim.

Diving regulators appeared as early as 1838, when Dr. Manuel Théodore Guillaumet invented a twin-hose demand regulator with a surface-demand use. A few more regulators were designed in the 1860’s, but they didn’t really take off.

It wasn’t until 1942, when Émile Gagnan adapted the Rouquayrol-Denayrouze apparatus into a regulator and then further adapted it to a diving cylinder.

The self-contained Aerophore diving apparatus was the inspiration for the diving suits Jules Verne described in his famous underwater adventure novel, “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.”

Louis Boutan, first underwater photograph

Louis Boutan, first underwater photographInterestingly, diving photography was also developed in the late 1800’s. In 1893. Louis Boutan invented the first underwater camera and made the first underwater photographs.

In the late 1800’s industry began to develop high-pressure air and gas cylinders. The works of Paul Bert of France in 1878 and John Scott Haldane of Scotland, explained the physiological effects of water pressure on the body, and are the basis of the majority of modern decompression theories. Technology improvements of compressed air pumps, carbon dioxide scrubbers, regulators, and more were being made at the same time. All combined these have made it possible for people to stay under water for long periods. To compliment these advances, the 1930’s saw the development of fins and masks made out of rubber, with glass inserts for the masks.

Finally, in 1943 Gagnan and Jacques Cousteau patent the first modern demand regulator. This development was a significant step in the development of Scuba, and the beginnings of making diving accessible to the masses.

National Geographic Magazine published an article in 1953 about Cousteau’s underwater archaeology at Grand Congloué Island near Marseille. This was the beginning of public demand on a mass scale for diving gear. In the 1950’s, the sport of diving began to change from breath-hold to mainly scuba and dive stores open up around the US.

By the 1970’s, equipment like BCD’s (buoyancy control devices), pressure gauges, and single hose regulators became standard equipment. Dive computers entered the scene in the 1980’s, making the diving experience easy and even more fun.

Today there are two principle types of scuba, open and closed circuit. Recreational divers primarily use the open circuit system, where the air is expired into the water. The closed circuit system utilizes rebreathers. This is where the exhaled air is re-breathed after carbon dioxide is absorbed and oxygen added, creating no bubbles in the water. This is used by military divers, and is now available to recreational divers as well.

The History of Diving Museum is a wonderful place to visit and learn some incredible facts about diving throughout history. Additional information was drawn from the articles: The Early History of Diving by MarineBio, along with A Brief History of Diving: Free Divers, Bells and Helmets Part I

and A Brief History of Diving, part 2: Evolution of the Self-Contained Diver by Dive Training.

Clarice Brough is a team member at Animal-World and has contributed many articles and write-ups.