Giant Clams are beautiful and hardy in the aquarium, but there are some ailments to be on the watch for to keep a happy healthy clam!

In the wild, small giant clams are heavily preyed upon. Other clam ailments include irritants and disease. Because most of the clams available to aquarists today are juveniles, hobbyists must still be extra cautious. With proper clam care and being able to identify clam ailments and problems you will have a happy healthy clam.

Clam ailments and problems are explored here, but to learn how to: Obtain a healthy clam, Provide good clam care, Identify clam ailments, and Prevent clam problems: See Caring For Tridacnid Clams.

Predators:

Predators include many species of fish. They may pick at the clam or eat its mantle. Some of those to avoid include triggerfish, large wrasses, and puffers. Blennies, butterfly fish, clown gobies, angelfish and constantly grazing fish may also disturb giant clams.

Other predators include species of crabs, lobsters, and shrimp, polychaetes (Bristleworms, Fireworms, etc.), octopi, and snails. Evem some burrowing sponges will prey on clams. Polychaete worms, often referred to as ‘clam worms’ such as the larger Nereis sp. and Eunice sp. can prey upon gaint clams.

Irritants: Though predators are often the primary source of problems for giant clams, you must also watch out for tank inhabitants and growths that can irritate clams. Irritants include algae, sweeper tentacles of stinging corals, Aiptasia anemones allowed to grow on clams, and the noxious by-products of some soft corals. Even air bubbles rapped inside the clam.can be an irritant.

Clam diseases:

Clam diseases can be seen in bleaching, poor tissue expansion, and the mantle pulling away. A natural defense of giant clams when irritated is to produce large amounts of clear mucus, or they can release Zooxanthellae.

Aiptasia Anemones

Photo © Animal-World

Photo © Animal-WorldPhylum: Cnidaria

Class: Anthozoa

Subclass: Zoantharia

Order: Actiniaria

Genus: Aiptasia spp.

Common Name:Glassrose Anemones – Aiptasia Anemone

Everyone knows about these small anemones and the scourge of the reef tank that they can become if allowed to gain a foothold in your tank. Aiptasia can sting and irritate a clam to death, so take whatever means are necessary to rid your tank of them.

Some methods of Aiptasia removal:

- A more natural way – find something that eats Aiptasia in nature and won’t go after anything else in your tank.

- Add Peppermint Shrimps (Lysmata wurdemanni) – watch out for your other zoanthids like the Yellow Polyp

- Try adding a Copperband Butterflyfish (Chelmon rostratus) – watch out for your annelids like feather duster worms

- Add a Caribbean nudibranch (Spurilla neapolitana or Dondice occidentalis)

– the first nudibranch should only be put in a tank with no other corals or anemones (a new setup)

– the second nudibranch “may” not bother other anemones or corals. - Other methods include injecting products like Chem-Marin’s Stop Aiptasia or kalkwasser into the Aiptasia itself.

A word of warning, any damage done to Aiptasia will result in a population explosion – so don’t try to scrub them off your rocks! It’s a battle!

Algae

Macroalgae like Caulerpa can irritate the clam if it is allowed to grow under the byssal opening. Algae that cover everything, including your clam, will block out its light source and lead to, if not cause, its death. This is particularly true of that pest, hair algae.

Bacteria – Viruses

There hasn’t been too much research on the kinds of bacteria and viruses than affect corals and clams. It is obvious that this research is needed as bacteria and viruses could be more devastating than what storms and humans do. More research has been done on bivalves (mussels and oysters in particular) because, simply, they represent billions of dollars in cash crops.

Very few studies have been done on pathogens affecting tridacnids. There are a number of bacteria, pathogenic and non-pathogenic, that affect tridacnid clams. Vibrio alginolyticus and V. anguillarum have caused deaths in larval and adult oysters. These organisms are also commonly found in healthy clams.

Bacterial infections are thought to have caused mass deaths of larval cultured tridacnids in Australia. Antibiotic treatments proved effective for increasing the survival of tridacna clam larvae. Bacterial and viral diseases are very difficult to identify and treat. Many treatments can stress or kill the other inhabitants of a reef tank.

Bristleworms – Fireworms

Phylum: AnnelidaClass: PolychaetaCommon Name:Bristleworms and Polychaetes – Clam Worms

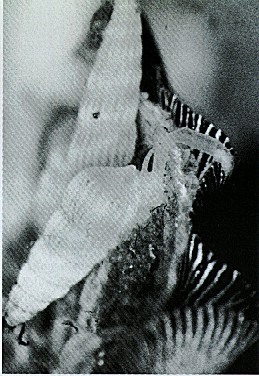

Many polychaetes are carnivores or omnivores and have strong, chitinous jaws that can be extruded from a protrusible pharynx. The two main genera that cause trouble are Eunice and Nereis. Larger species can reach up to 20 inches (50 cm) in length.

These large worms can cause a good deal of damage in the aquarium. They are recognizable by their pronounced body segmentation, parapodia and setae. They are mainly active at night and are usually added to the tank hidden within the live rock. Both Eunice and Nereis will feed on corals, clams and even small, sleeping fish.The Fireworm (H. carunculata) also preys on corals, anemones, and clams and should be removed as soon as possible.

Order: Eunicida

Family: Oenonidae

The polychaete Oenone fulgida eats snails and clams. Approximately 0.1 inch (0.25 cm) in diameter and 4 to 12 inches (10 to 30 cm) long, this worm is bright orange in color and secretes a mucus which it uses to trap and suffocate snails, eating the tissues when the snail dies.

This worm attacks clams by boring a perfectly round hole in the clam’s shell and feeds on the living clam’s tissues. The worm retracts into the live rock and returns to it’s meal through the same hole or bores a new one. A healthy clam can block the hole with a protein matrix and seal it with new calcareous shell. The clam, now weakened, eventually gets an infection and dies.

This worm is common in live rock and the only way to remove it from your tank is to remove the rock it retreats into.

True Crabs

Pea Crab Photo © Robert M. Metelsky

Pea Crab Photo © Robert M. MetelskyFamily: XanthidaeCommon Name:Stone Crabs

Crabs in this family are mostly carnivorous. Bristle Crabs (Pilumnus spp.) is one genera that can cause considerable damage to a reef tank.

These crabs are tiny and have a dense covering of bristles over the majority of their legs and claws. They eat nearly anything in a reef aquarium – clams, stony and soft corals, anemones, and tube worms.

Family: Calappidae Common Names:Box Crabs and Shame-Faced Crabs

These crabs prey on molluscs such as clams and snails. They will quickly eliminate your herbivore snails.

These crabs are recognized by the depressions in their shells which they retract their legs, claws, and eyes into. This gives them a box-like shape. They are also called Shame-Faced Crabs because the retracted claws are so broad and flattened that the crab’s face is hidden. They are brightly colored with pink or red patterns on their carapace.

They are normally found buried in the sand and are rarely encountered in aquariums. They shouldn’t be kept in reef tanks since they will eat almost anything.

Family: PinnotheridaeCommon Name:Pea Crabs

These crabs live in molluscs and are rarely encountered. Mostly living in harmony with their host clam, they are always found in male and female pairs. They spend their entire life in their host.

Lobsters

Suborder: ReptantiaSection: Macrura Common Name:Lobsters

Most of the small lobsters for sale to hobbyist belong to the genera Enoplometopus (Reef Lobsters) or Panulirus (Spiny Lobsters). These are omnivorous scavengers and can be destructive to your reef tank. They will feed on your clams, corals, small fish, shrimp, and probably many other inhabitants of your tank.

Protozoa

Phylum: ProtozoaSubphylum: Ciliophora Common Names:Ciliates and Protozoans

To explain best what a protozoa is I’ll use an example, “brown jelly”. This protozoal infection usually attacks corals.Tridacnids collected throughout the Great Barrier Reef have been found to contain a protozoa from the genus Perkinsus. This protozoa’s role in clam deaths is unknown. Also, an unidentified ciliated protozoan was found that invades the mantle and ingests the zooxanthellae.

Mantis Shrimp

Odontodactylus scyllarus – Mantis ShrimpPhoto © Jeffrey Rosenfeld

Odontodactylus scyllarus – Mantis ShrimpPhoto © Jeffrey RosenfeldPhylum: ArthropodaClass: CrustaceaSubclass: MalacostracaSuperorder: HoplocaridaOrder: StomatopodaCommon Names:Mantis Shrimp and Thumb Splitters

Added to your tank with live rock, these “shrimp” are voracious predators and will feed on small fish, shrimp, worms, clams and crabs. Just about any living, or once living, creature in your tank is a meal to this thing.

There are many species, ranging from 2 to 12 inches (5 to 30+ cm) in length. The smaller genus, Gonodactylus, are the ones most found in aquarium.

Methods of removal include: baited traps, removal of their rock lair, using sharp, pointed scissors to skewer or cut the shrimp in half, and more.

True Shrimp

Superorder: EucaridaOrder: DecapodaSuborder: NatantiaFamily: HippolytidaeCommon Names:Marble Shrimp (Saron marmoratus)

They are large, reaching 3.6+ inches (9+ cm) in length. Shy and nocturnal, they can attack tridacnids, corals, mushrooms, anemones and small polyped corals (eg. zoanthids).

Snails

Phylum: MolluscaClass: GastropodaCommon Name:Snails and Sea Slugs

These critters are usually added to your tank with shipments of live rock, corals and clams. These must be removed immediately or they will make a quick meal of your tank’s clams, corals, gorgonians, anemones, and zoanthids. The hardest part of doing this, is recognizing a predatory snail or figuring out that a sick coral is the result of snail attacks!

Prevent this problem by examining each and every item you put in your tank carefully.

Family: CymatiidaeCommon Name: None

Cymatium muricinum is a known clam predator. It is a problem for clam farms that are ocean based. Found throughout the Indo-Pacific and in the western Atlantic, adding it to your tank with a live rock shipment is a possibility

The snail’s larvae settle on the tridacnid and undergo metamorphosis. The snails enter through the byssal opening and lodge between the shell and mantle.

The clam shows little reaction to the snails presence as it begins to feel on the mantle’s juices. The clam will eventually react by closing its valves and it may even try to enclose the snail inside a pearl-like blister. Eventually the clam exhibits wide gaping and dies.The grown snail moves on in search of another victim.

Large snails, 1 to 2 inches (25 to 50 cm), wait at the bottom of the clam, next to the byssal opening, extending their proboscis into the opening and feeding on the tissue inside. Larger clams are usually not bothered by these snails because their weight presses the byssal opening down into the substrate so deeply that the snails can’t reach it. Also, Hippopus spp.‘s byssal opening is usually too small to allow these snails entry.

Order: PyramidellaceaFamily: Pyramidellidae Common Name:Snails

Pyramidellidae Snail Provided by Harbor Aquatics

Pyramidellidae Snail Provided by Harbor Aquatics A Majority of the snails that feed on clams and oysters belong to the family Pyramidellidae. There are a least 1000 species in the Pacific alone

These are small snails with a maximum length of 0.08 to 0.16 inches (2 to 4 mm) and they look like small grains of rice. Majority of what we know about these snails is from the species that have been found feeding on oysters and clams in commercial setups.

Very little is actually known about how many species affect tridacnids. Tathrella iredalei and Pyrgiscus sp. are two species that were isolated in Australian clam farms. Studies of Pyrgiscus in aquaculture systems show it to have an very rapid reproduction rate when in land-based seawater tanks or in trays raised about the substrate in the wild.These snails are simultaneous hermaphrodites.

A 0.1 inch (2.5 mm) snail is capable of producing 2 to 3 egg masses a day. Each egg mass has up to 120 eggs. The eggs are held in jelly-like masses on the clam’s shell. There are often several egg masses close together. The young snails tend to remain on the clam they hatch on.

Pyramidellidae snails feed mostly at night. During the day they stay out of direct sunlight and can usually be found near the base of the clam or between the scutes in species with large scutes (eg. Tridacna squamosa). At night, they work their way up to the lip of the shell and extend their proboscis and, using their needle-like stylus, poke a hole into the mantle of the clam. They then suck out the fluid of the mantle.

Depending on the size of the clam, these snails can easily kill it within days or months if left unchecked.According to the Reef Aquarium Volume One by Delbeek and Sprung, these snails are relatively rare in the wild which means that some type of biological control must be in place.

Some natural predators of these snails are:

- Portunid crab (Thalamita sima). These crabs have been used in aquaculture systems with some success. Unfortunately, they have also been known to feed on small (1.6 inch / 4 mm) tridacnids.

- Halichoeres Wrasses. Specifically H. melanurus and H. chloropterus have been seen feeding on these snails in the wild.

- Six-Line Wrasse (Pseudocheilinus hexataenia) and Four-Line Wrasse (P. tetrataenia) have been known to eat these snails in the aquarium.

Unless the snails are visible on the shell during the day, the fish won’t be able to see them. Since these snails are nocturnal, removal by the hobbyist may still be needed.

Disease – Disease Like Symptoms

Bleaching

A bleached clam will appear white, pale yellow, or pale green. The tissue is still alive, but the loss of zooxanthellae makes the it look transparent. Clams that have undergone bleaching appear generally less healthy and may show poor tissue expansion. Sometimes, with bleaching, there is no loss of zooxanthellae, just a decrease in the pigment content. Pigment reduction is related to changes in light intensity. Zooxanthellae expulsion occurs with temperature changes.

Sudden bleaching can occur when exposed to water that is too hot (over 86oF or 30oC) or too cold (below 66oF or 19oC). This can also happen if the light field has changed radically. Inadequate or too much light can lead to slow bleaching.

Clam bleaching can also be caused by the excessive use of activated carbon and the reduction of trace elements, especially iodide. This is most common in stony corals, but can occur in clams and soft corals. Iodide loss can cause rapid bleaching and death.

Broken Hinge

A break in the brown protein material that joins the two shells happens rarely. Re-align the shells and place a rubber band loosely around them to hold the hinge position. Make sure the rubber band isn’t too tight – the shells need to be able to part far enough for the mantle to extend and receive light. In about two weeks, the clam will secrete a new hinge.

Brown Mucus

A clear, brown, thick gelatinous mucus is sometimes found around the byssal opening. The clam is trying to protect itself from contact with irritating substances (ex. coral mucus) and keeping worms, snails, and crabs, etc. away. Although considered a harmless condition, I would make a definite effort to find any possible irritating critters.

Excess Mucus

Giant clams normally release some clear mucus from around their mantles and upper surfaces. The mucus often has some air bubbles within it. The clam is getting rid of excess carbon from photosynthesis. The irritation may be from something in the water or form a nearby coral. Excessive mucus can clog mechanical filters and is a sign of irritation.

Avoid handling your clam since you don’t want to irritate it anymore, but provide it with a stronger flow of water – remember clams don’t like a strong current so only do this to remove the excess mucus. If this doesn’t clear up the problem, do some water changes and add some good quality carbon. Obviously, if the clam is being annoyed by a coral, move the coral.

Hole in the Mantle

Your clam may develop a hole in the center of its mantle, between the inhalant and exhalent siphons. This is potentially fatal but usually heals and may or may not leave a scar. Move your wounded clam and make sure it is not being preyed upon. Healing should occur within a few days. The causes include:

- Physical injury. Infection (bacterial or protozoan).

- Light damage. Placing your clam less than 8 inches from a metal halide bulb can result in a burn which causes a hole to develop. These bulbs can also burn your corals. Metal halides kept more than 8 inches from your tank will not cause this problem.

Poor Tissue Expansion

Sometimes a clam won’t expand fully and may remain contracted for several days or longer. There may be a number of reasons for this happening:

- A pH that is too high or too low. Maintain a pH between 8.0 and 8.5. Too strong or too weak water current. Being downstream of a coral releasing terpenoids into the water. Move the coral or the clam. If more of your tank’s critters are affected, use protein skimming, carbon, and water changes to remove the compounds from the water. If this doesn’t work, the offending coral will have to be removed from the tank.

- Stinging sweeper tentacles from neighboring corals. Move the coral away from the clam.

- Fouling or over-growth of algae, bacteria or mucus. Siphon the stuff away and alter the water flow around the clam.

- Being irritated by a fish or other tank inhabitants.

- Excessive UV light. Move the clam lower in the tank and make sure iodide is being added in proper quantities. You may need to put UV shielding between your lights and the tank.

- Too intense light. Move the clam lower in the tank.

Releasing Zooxanthellae

Giant clams have been known to release packets of zooxanthellae from their exhalent siphons. These packets will look like dark brown strings or pellets. This is a sign that the clam is regulating its population of zooxanthellae.

This may happen from time to time. You can expect it when you first add the clam to your tank or if you move it around within your tank.

Also, changes in the clam’s environment (temperature, light intensity and spectrum) will cause the clam to readjust it’s zooxanthellae population. It is possible to shock your clam with too great a change (too much or too little light or a photoperiod that is too long or too short). The shock may cause the clam to expel all of it’s zooxanthellae. This is known as bleaching.

Almeja gigante (Tridacna maxima) (Image Credit: Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 International)